Grafted Titans: I Built a Plug-and-Play Neural Memory for Open-Weight LLMs

Using only an Nvidia DGX Spark Blackwell for €4,400

I am splitting this research into two parts. This article is the non-technical overview.

For the engineers and scientists, the deep dive is coming next. In the coming days, I will open-source everything: the code, the model weights, and the full mathematical framework. I am taking a little extra time to ensure the technical documentation meets a rigorous scientific standard. Stay tuned.

Executive Summary: Grafted Neural Memory for Everyone

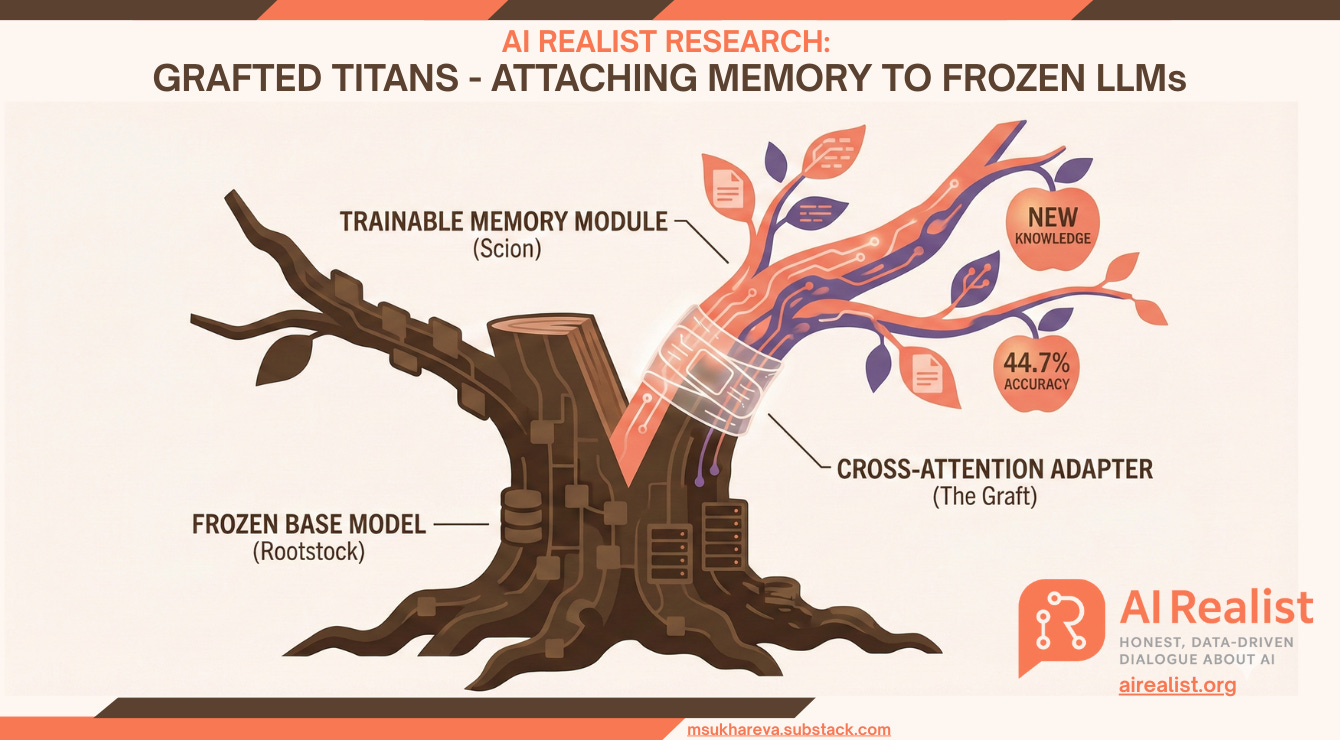

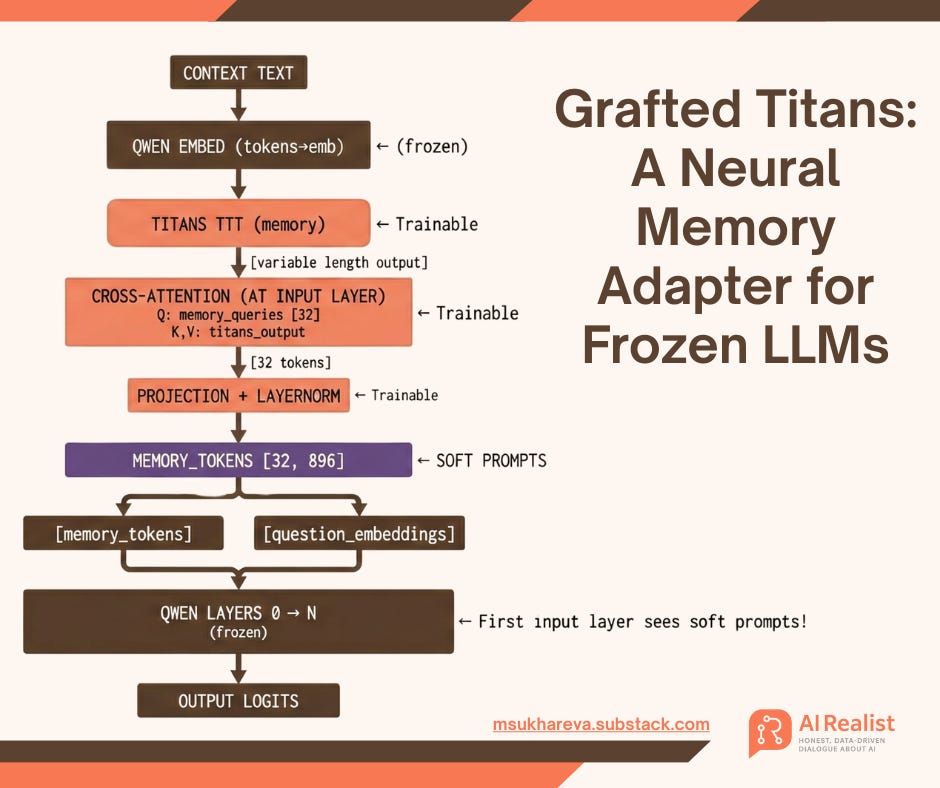

This research introduces “Grafted Titans,” a novel architecture that solves the critical inability of LLMs to learn continuously from user interactions without the crippling costs of traditional retraining. By “grafting“, I mean attaching a trainable memory module to a frozen model.

By “grafting” a dynamic Neural Memory module onto a frozen, open-source model (Qwen-2.5) via a lightweight cross-attention adapter, I have created a system that can instantly memorize and retrieve new information with 44.7% accuracy on complex tasks, a massive improvement over baseline, while running on a single consumer-grade GPU (€4.4k hardware). This approach effectively democratizes Google’s cutting-edge “Titans” research, transforming it from a multi-million dollar industrial ambition into a plug-and-play solution that any business can use to build adaptable, personalized AI that “remember” their users, bypassing the noisy bottlenecks of RAG and the immense compute costs of infinite context windows.

Upgrade your subscription to support this newsletter!

Also, check out our website for services, training, advisory etc:

Paid subscribers get:

Priority answers to your messages within 48-hours

Access to deep dives on the latest state-of-the-art in AI

Founding members:

A 45-minute one-on-one call with me

High-priority personal chat where I quickly reply to your questions within 24-hour

Support independent research and AI opinions that don’t follow the hype.

— or check out the shop

Motivation

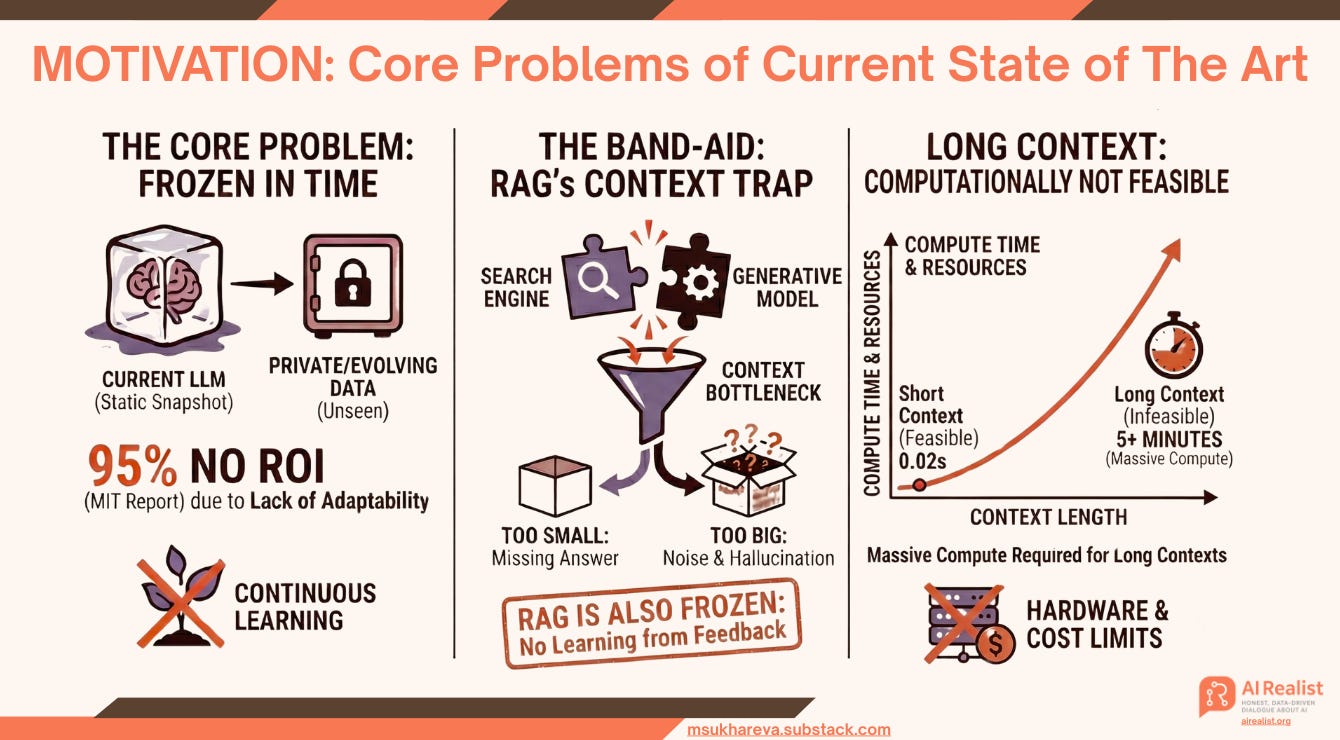

The fatal flaw of current large language models (LLMs) is that they do not learn continuously. They are typically trained on a massive snapshot of data and then frozen in time. When a user interacts with a model, it cannot adapt its weights to new information, nor can it remember corrections from previous sessions. While this static nature is acceptable for general-purpose queries, it represents a critical failure for domain-specific tasks, particularly when processing private, evolving company data that the model has never encountered. An MIT report names this lack of adaptability as one of the major reasons why 95% of AI projects fail to pay off.

To mitigate this, the industry relies on “band-aids” like Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). However, RAG fundamentally attempts to force compatibility between two distinct systems: a search engine and a generative model. This integration introduces a bottleneck regarding context size:

Too Small: If the retrieved context is too short, the relevant answer is missing.

Too Big: If the context is too large, the model is flooded with noise, significantly increasing the risk of hallucination.

RAG is also frozen in time in its own way and does not learn. At best it can augment the knowledge base with your feedback but it does not essentially learn anything about the importance of your feedback or that the previous answer was wrong.

Furthermore, in-context learning has a big drawback - the longer the context, the more expensive is the computation. The attention mechanism in Transformer architectures scales quadratically:

meaning that doubling the context length quadruples the computational cost and memory usage.

For example, processing a prompt with a 4k context size on a Qwen-2.5-72B (or Llama-3-70B) running on a single Nvidia Blackwell (128GB VRAM) takes merely 0.02 seconds. In contrast, processing a 2,000,000 context size on the same model would take 5 minutes of pure compute time.

Huge contexts are hard to use in daily life as they needs substantial computational power and a lot of providers that announce millions token context windows cap it to no more than 100k

Test Time Training

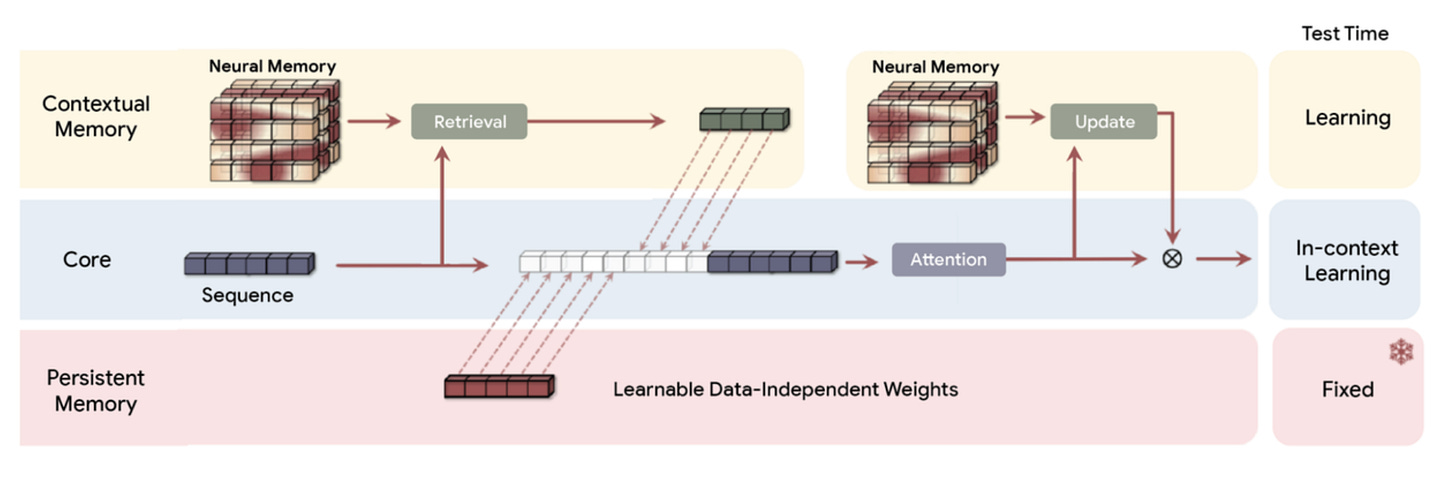

The latest research focus has shifted sharply toward Test-Time Training (TTT). Particularly, Google’s cutting-edge Titans architecture (and its newer “Hope” variant) has received massive attention.

This architecture integrates a separate neural memory directly into the Transformer. Unlike standard models, this neural memory learns on the fly, meaning it can memorize new information instantly and use it for subsequent answers. Previously, this was the third rail of deep learning: any attempt to fine-tune a model live would shift the weights and damage the model’s core abilities, causing “catastrophic forgetting.”

Google’s work signals a new era for domain adaptation. Titans’ memory approach allows networks to learn during inference, theoretically overcoming the limitation of frozen weights and knowledge cut-offs.

The problem is: the research is still in the lab and is not directly adaptable for us yet. The approach requires a surgical decomposition of the base model, projecting attention layers of memory onto every layer of the transformer. Because the base model must train together with this memory module, it is computationally expensive and impractical for most real-world applications today.

This is the major limitation: it’s not a plug-and-play solution; it demands deep, expensive architectural integration.

AI Realist Research: Titans Memory For Everyone

Today, I am proud to present my own research, which I believe is a critical step toward the practical usage of Titans memory. This approach makes Test-Time Training (TTT) accessible to everyone, effectively signaling a new era of neural LLMs - adaptable, efficient, and user-centric.

My Main Contributions:

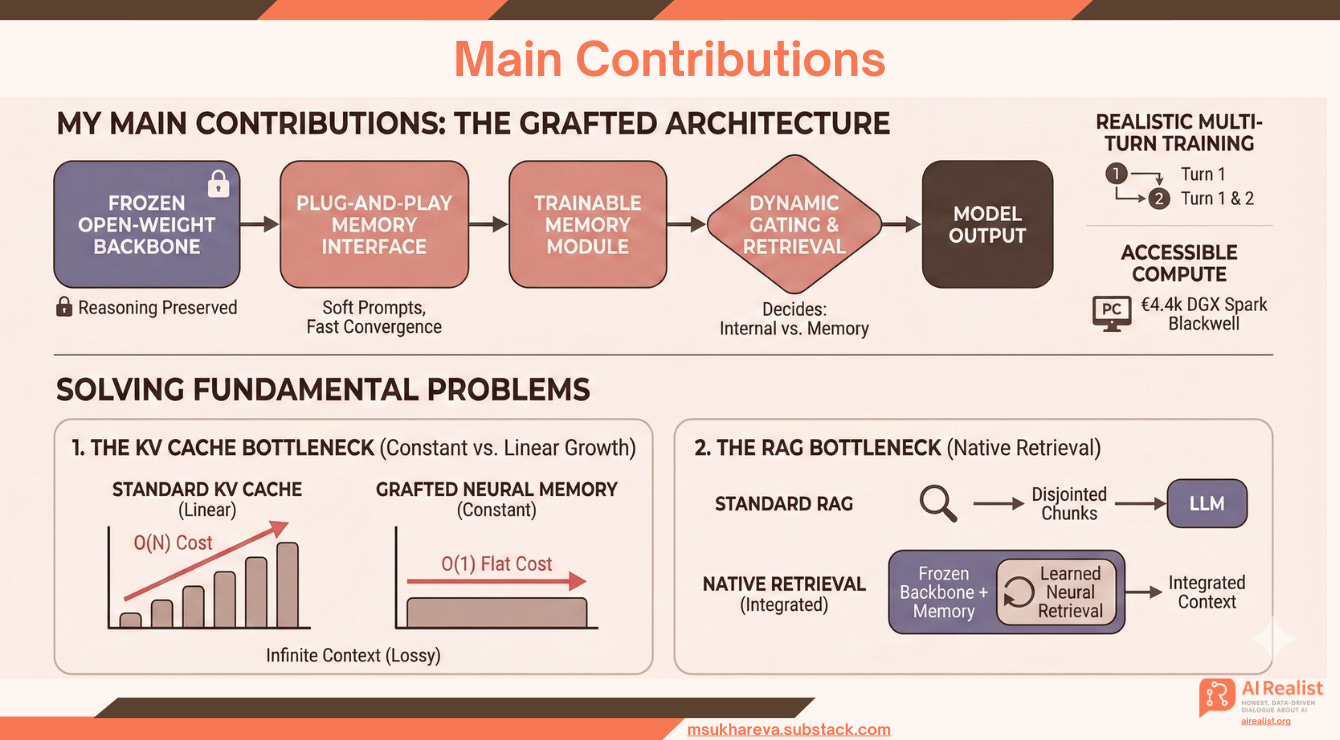

Frozen Open-Weight Backbone: Instead of training a base model from scratch, I utilize Qwen-2.5-0.5B with fully frozen weights. This drastically reduces the cost and complexity of training, preserving the model’s reasoning baseline.

Plug-and-Play Memory Interface: Rather than projecting memory onto every layer of the base model (as in the original paper), I apply a cross-attention mechanism at the first input layer. The memory weights are appended to the Qwen model as “soft prompts,” creating a modular architecture that converges faster.

Dynamic Gating & Retrieval: The memory module trains alongside the frozen backbone. The cross-attention and native gating mechanisms ensure the model learns to dynamically decide when to use its internal knowledge and when to query the neural memory for specific details.

Realistic Multi-Turn Training: Unlike the Google research, I implement a realistic multi-turn setup. The context is provided in the first turn (memorization phase), and the answer is queried in the second turn (retrieval phase). This forces the model to strictly differentiate between the immediate prompt context and the compressed neural memory context.

Accessible Compute: I trained this entire architecture on an Nvidia DGX Spark Blackwell with 128GB VRAM - a portable desk supercomputer costing only €4.4k. This demonstrates that effective memory utilization does not require massive industrial clusters.

I believe this experiment demonstrates that Grafted Neural Memory can solve two fundamental problems inherent in current LLM-based architectures:

1. The KV Cache Bottleneck (Constant vs. Linear Growth)

Unlike standard KV caching, which grows linearly with context length and slows down inference, this architecture maintains a constant memory size.

The Trade-off: Standard KV caching is a lossless approach that hits a “computational wall” as context expands.

The Solution: My approach is a lossy compression strategy. By compressing history into a fixed set of tokens, it theoretically supports infinite context without ever increasing computational complexity. The cost of memory retrieval remains flat O(1), regardless of whether the context is 10k or 1M tokens.

2. The RAG Bottleneck (By Introducing Native Retrieval)

This architecture solves the “Search-LLM mismatch” of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and offers a viable alternative.

The Problem: RAG is bottlenecked by the quality of external search algorithms, which are designed for keyword retrieval, not neural reasoning. RAG never shows the model the full context; it shows disjointed chunks. If the retriever fetches the wrong chunk, it forces the model to hallucinate. Furthermore, RAG is still bound by the context window limits of the LLM as discussed above.

The Solution: Neural Memory acts as a retrieval mechanism that is native to the LLM. Instead of relying on an external database, the model learns to store and retrieve its own information. This is the architecture I have been advocating for years: Retrieval and Reasoning must be built together. That is exactly what I am doing here.

Experimental setup

I use the Qwen-2.5-0.5B-instruct model as the base for this experiment. It is crucial in this setup to utilize a base model that has already been fine-tuned for instruction following to maintain conversational coherence. The decision to use such a small model is strictly motivated by computational constraints, as I am currently operating with a single DGX Spark Blackwell. The training of just one epoch took 15 hours, resulting in a total run time of 150 hours for 10 epochs. While I believe that using a larger base model alongside a larger neural memory network would yield superior results, these were the practical limits of the available hardware.

For the memory architecture, I follow the unofficial implementation of the Titan memory published by lucidrains. The Titan memory is trained from scratch, meaning I rely on random initialization rather than pre-trained weights. During the experimental phase, I attempted to zero out the last neural layer to ensure the noise from the randomly initialized memory did not overwhelm Qwen. Unfortunately, this strategy failed; Qwen simply started ignoring the memory stream entirely rather than learning to denoise it. The original Google paper solves this by jointly pre-training the memory module with the core model, which ensures the memory network starts with learned compression patterns. This is a valid and likely necessary path for future research, though I did not implement it here as I am operating on frozen core model.

Major contributions to the architecture:

Soft prompting of the input layer with memory embeddings. Following the foundational approach of Lester et al. in “The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning”, I append the memory embeddings directly to the first input layer of the Qwen model. Crucially, the Qwen embeddings remain frozen throughout the entire training process. I train the memory on the BABILong dataset, restricting the context window to 2,000 tokens. This limit was necessary because training on a larger window caused the time per epoch to balloon to 34 hours. For a proof-of-concept, the 2,000-token length is sufficient, though future research with higher computational resources would certainly target larger contexts.

Cross-attention mechanism. To ensure the architecture can accurately judge when to use memory and when to rely on the model’s internal knowledge, I train a cross-attention gating layer. The purpose of this layer is to dynamically decide the weight of the memory for any given query. This learned gating mechanism is significantly more efficient and robust than setting a static hyperparameter to control how much the model relies on the memory.

I hypothesize that this cross-attention mechanism is the primary reason I achieve such high accuracy (~45%) on exact word retrieval from BABILong, despite using a highly compressed, lossy setup. While standard soft prompting "smears" details into a general gist, the cross-attention layer acts like a signal amplifier (This mirrors the core finding of Google's Titans research as their architecture succeeds precisely because it deeply integrates memory into the attention layers. By replicating this "attention-as-retrieval" mechanism in a lightweight form, I enable the model to actively "search" its memory rather than passively receiving it.). It can extract and reconstruct faint, specific signals (like an exact passkey) from the compressed memory embeddings that would otherwise be lost in the noise. It bridges the gap between the "blurry" nature of soft prompts and the precision required for retrieval.

Evaluation and Results

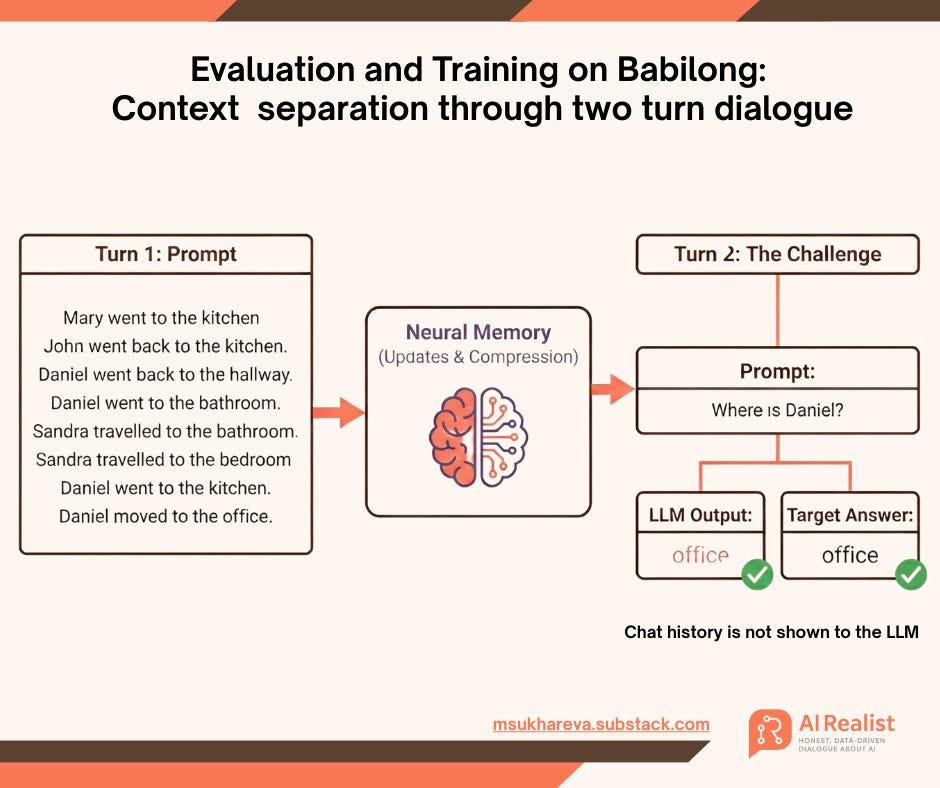

The evaluation is conducted on a held-out subset of the BABILong dataset, using a strict two-turn protocol to ensure no information leakage. In Turn 1, I feed the context to the model via a prompt. This prompt passes through the architecture and into the neural memory, which adapts itself by updating its internal weights on the fly. In Turn 2, the model receives the question.

Crucially, the original context is completely removed for this second turn. Unlike standard RAG or long-context approaches where the model can “look back” at the chat history or retrieved chunks, here the model gets nothing but the isolated question. The only way for it to answer correctly is to retrieve the specific fact from its neural memory.

To understand the significance of the results, we must look at the baseline. On this specific BABILong task, a model relying on random guessing achieves approximately 0.67% accuracy, which is basically - everything is wrong except for one random guess. Another baseline was the predictions by Qwen when the full context is provided. That baseline achieves 34%.

Monitoring the learning progress on the validation set reveals a clear trajectory. The model begins with significant noise and near-zero accuracy, effectively hallucinating. As training stabilizes, it climbs to 22%, proving it has moved beyond random guessing and is beginning to form coherent memory structures. As training continues, the accuracy climbs to 44,7% by the 9th epoch!

The Critical Finding: This result is counter-intuitive and profound. My grafted memory system outperformed the vanilla model that had the full text in its context window (44.7% vs 34.0%).

This suggests that for smaller models (like the 0.5B), a raw context window is not always the best way to handle information. The model’s native attention mechanism gets overwhelmed by 1,500 tokens of text. In contrast, the Grafted Neural Memory acts as a denoising filter, compressing the noisy narrative into clean, retrievable signals.

Frankly, this result exceeded my expectations. Given that the neural memory was not pre-trained but initialized from random weights and that the entire setup relies on a lightweight model tackling the complex BABILong benchmark achieving 44,7% accuracy confirms that the “Grafted Titans” architecture is genuinely learning to retrieve!

Implications for practical usage

I believe that my approach is a great foundation for integrating Test-Time Training (TTT) models for wider usage. The computational resources needed to train this memory are accessible to most research institutions, companies, and even owners of high-end private PCs. It is fundamentally different from the current state-of-the-art proposed by the Google research team, which assumes a multi-million dollar training run of a bespoke Transformer model from scratch.

To my knowledge, I am the first to propose a plug-and-play inference-time memory for frozen, pre-trained base models. Depending on the available compute, this approach can essentially be used with any open-weight Transformer model on Hugging Face (I will publish the code repository and the weights). Furthermore, thanks to the Gated Soft-Memory Injection mechanism (my enhanced version of soft prompting appended through cross-attention), I see massive potential for distributing pluggable Titan memory modules for specific architectures like Qwen, Llama, etc.

Crucially, this architecture resolves the inference latency bottleneck. Unlike the full Titans model, which requires heavy sequential updates during generation, my grafted memory acts as a lightweight adapter. It adds negligible latency, only the cost of a single cross-attention pass per query, making it viable for real-time applications where speed is non-negotiable.

Limitations

1. The “Two-Turn” Limit

Current benchmarks can be deceiving. My setup is trained and evaluated on BABILong, which essentially tests a “Store —> Retrieve” loop in 2 turns. While this proves the mechanism works, it does not prove stability. We simply do not know how the memory behaves in a truly multi-turn conversation (10+ turns). Does the memory saturate? Does earlier information get overwritten by later noise (”catastrophic forgetting” on a micro scale)? A true production system needs to be tested if it can keep much more information in the memory.

2. The “Gullible Memory” Risk and No Guardrails

Currently, this architecture implements zero guardrails against memory corruption. It treats every user input as absolute truth. If a user (or a malicious prompt injection) states “The sky is green” in Turn 3, that data is encoded into the neural memory weights as a fact. In Turn 4, the model will hallucinate based on this poisoned data. Without a “verification layer” or a “truth discriminator” to filter incoming information, this setup is highly vulnerable to Memory Poisoning and conflicting data. This is an area for future research.

3. The Vanishing Gradient (Signal Dilution)

I must also address the critical architectural drawback of my grafted approach: Signal Dilution. By injecting memory primarily at the input level (Layer 0) via soft prompting, we face a “distance problem.” The memory signal must propagate through all 32+ layers of the Transformer to reach the output, risking a “vanishing gradient” effect. The larger the base model, the higher the risk.

While my cross-attention gate acts as an amplifier to mitigate this, it is not bullet proof. Future research should explore multi-layer injection that is grafting memory adapters at higher layers (e.g., the middle or final blocks) to shorten the path between retrieval and reasoning. I encourage readers to fork my neural memory implementation once I publish it, adapt it to their needs, and help solve this signal dilution challenge.

4. Production Readiness

Let’s be clear: this is a research prototype, not a production microservice. Moving this to production would require solving the signal dilution problem and building a robust filtering mechanism to prevent the memory module from becoming a trash can of conflicting user inputs. Until then, it remains a promising proof-of-concept, not a product.

Conclusion

In this article, I presented my latest research, which I believe represents a meaningful step toward addressing one of the major limitations of current large language models: their inability to dynamically learn from users and adapt to new information. I argue that plug-in lossy memories, added to a large and stable base model, can provide the level of personalization and domain adaptation that current band-aid approaches such as RAG and long-context extensions fail to deliver.

My results show that integrating a neural memory does not require complex or invasive modifications to the transformer architecture. Instead, it can be implemented as a plug-and-play soft prompt, connected to the input layer of the base model via cross-attention.

I also demonstrate that this architecture drastically reduces the computational resources required to create a Titan memory when training is restricted to updating only the neural memory weights. Training costs are reduced from millions of euros to a few thousand, making this approach accessible to a broad range of AI researchers and teams with limited budgets.

I therefore believe that this work will inspire and enable companies and research institutions to actively explore and study Titan memories.

Acknowledgements:

To the Community: First, a massive thank you to my subscribers on Substack and LinkedIn. The incredible popularity of my posts has encouraged me to spend almost all my free time on research, studying LLMs and writing.

To the Patrons: Second, I want to specifically thank my paid and Founder subscribers, as well as everyone who used my services at airealist.org. You are the investors behind this research. Your support directly funded the NVIDIA DGX Spark Blackwell, the Mac Mini M4, and the stack of software subscriptions I use daily to run these experiments. Without you, this hardware and this experiment would not exist.

Why I Publish Here: This direct support is exactly why I am releasing this research here first, rather than waiting six months for a conference review cycle. As always, I am publishing this work without a paywall. I believe that research which helps us understand the reality of AI should be open and accessible to everyone.

The signal dilution problem across 32+ layers is a massive engineering challenge that doesn't get enough attention in TTT discussions. Cross-attention at layer 0 is clever because it sidesteps the architectural surgery issue, but the vanishing gradient risk scales exponentially with model size. I built something similar last year using LoRA adapters mid-network and ran into the exact same 'gullible memory' issue when dealing with conflicting user inputs across sessions. The 44.7% vs 34% result is especially interesting becuase it suggests the memory module is functionally acting as a learnable denoising filter rather than just storage.That BABILong setup is brutal btw, forcing strict separation between context and memory actually proves the mechanism works.

This looks excellent.

The only comment I'd add is that limitation #2 (The Gullible Memory risk) isn't just about adversarial inputs. It also makes this approach somewhere between less than ideal and unusable for any inputs which change over time. Which, fortunately or unfortunately, a very large amount of information does.

For example, if it learns about a businesses core products & services, and the business discontinues some products and focuses on others, the memory seems likely to continue to retrieve old information. And since that old information was likely built up over time, then the od may very well drown out the new. At a minimum, this would dilute newer, more accurate information; at a maximum it would in some sense hallucinate about the past - even though it has information about the present in its memory as well.

So, eventually, memory architectures will need some mechanism to either automatically purge memories that are no longer relevant, or assign and adjust priorities to different memories over time. If I tell a human that our strategy has changed, they handle this automatically - they understand both that there's a current state and a historical state (both of which are valuable to remember, but for different reasons). LLM memory will eventually need to figure out how to do this as well.

Quick thought: What if the information placed into memory was time stamped, and when the memory contains multiple conflicting hits on a topic, it automatically prioritizes the most recent information over the past information? This seems like it would more closely match how us humans handle changing information over time - and might also provide a way to more easily counter adversarial information planted in the past.